A gentle introduction to Spain’s fiesta nacional

I’ve talked about the controversial topic of bullfighting in a previous post reviewing Ernest Hemingway’s classic novel, The Sun Also Rises. At the risk of repeating myself, I’ll say that I’m quite ambivalent towards the topic. No one can be immune to the bull’s immense suffering in the ring, of course, but I also try to be respectful to counterarguments that underline the artistry and pageantry of Spain’s so-called fiesta nacional, as well as its history, its importance to regional economies, etc. I’m not Spanish or even Hispanic, after all, so it’s not for me to be critical of a culture of which I’m merely a student. As such, I’m always looking for ways to educate myself on controversial issues.

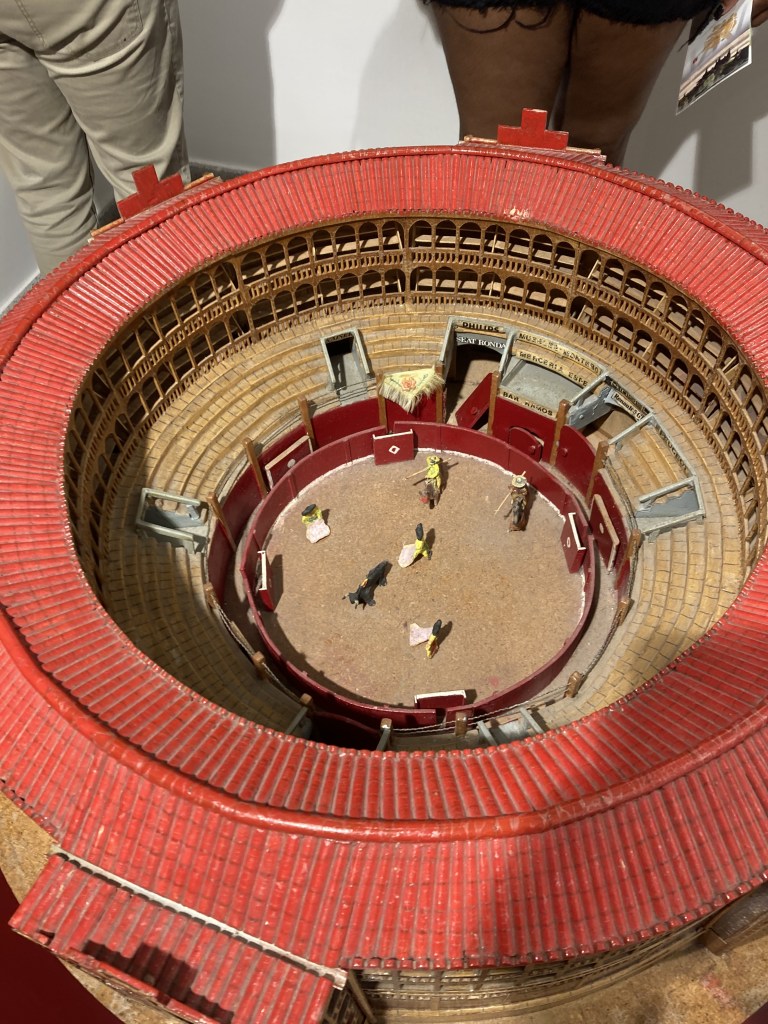

To that end, I took my family and some of my students with me recently to the Museo Taurino de Salamanca. Located adjacent to the majestic Plaza Mayor, the Museo Taurino is a small museum that offers visitors the chance to learn about bullfighting and its history and importance to this region of Spain. There are six permanent exhibits at the museum, each one highlighting a different aspect of bullfighting:

- The Dehesa (pasture/meadow used to raise bulls) and the Spanish Fighting Bull

- Salamanca’s Bullfighting History, Festival, Bullfighting Ring, and School

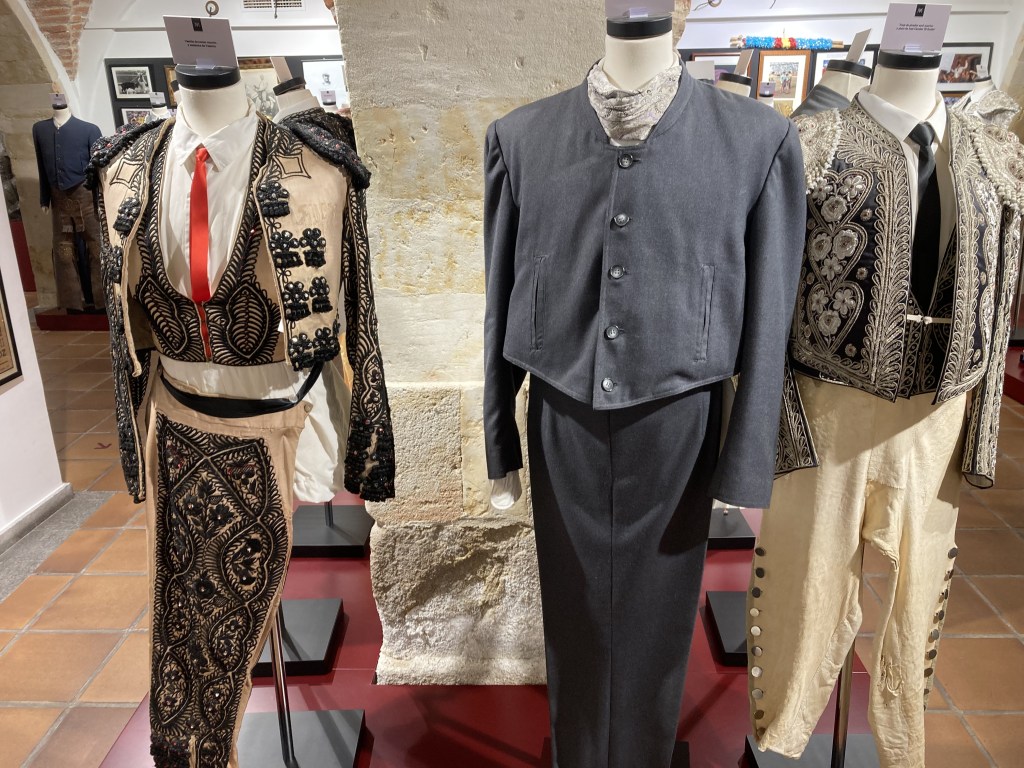

- Collection of Bullfighting Costumes

- Bullfighters from Salamanca

- Bullfighting and Art

- Audiovisuals of Salamanca’s Dehesa and Sample of Small Artifacts

One of the highlights for me was the opportunity to see the incredible details on the bullfighting costumes up close. I’ve had the opportunity to see my Mexican mother-in-law painstakingly create beautiful dresses, but I can’t imagine how much work goes into the creation of these one-of-a-kind outfits. The level of detail on them is astounding. They must cost a fortune! You can also appreciate the evolution of the costumes and the differences in the wardrobes worn by the different members of the torero‘s team. I’m struck by how uncomfortable they must be. They’re so tight fitting! I’m sure that loose fabric would make it easier for the bull’s horns to catch on, increasing the probability of being gored, thereby endangering the life of the bullfighter. I don’t know how they even walk comfortably in these outfits, let alone get out of the way of a powerful bull.

Coming from the Midwest of the USA, I’m used to seeing taxidermied heads of deer, elk, moose, and even the occasional bear in some of the homes I visit. In Spain, however, it is possible to find stuffed bullheads at restaurants and bars, and at the Museo Taurino de Salamanca, of course. I’ve never really understood the appeal of having taxidermied trophies in a home, but being so close to a bullhead in this setting lets you appreciate just how big the bulls are, and how scary it must really be to come face-to-face with one in a ring. The bullheads here include descriptions of where and when the bull was fought. And if you see a bull missing an ear, it’s because it was given as a somewhat macabre souvenir to the matador who was deemed to have a particularly skilled performance. The museum also has some of these bull ears, mounted as trophies, on display, too. You can also see up close the tools of the bullfighter – swords and capes – but for me, there isn’t a sword sharp enough that would make me feel protected against these powerful creatures.

Regardless of one’s opinion of bullfighting, it’s hard not to appreciate the artwork that was inspired by the fiesta nacional. Below are a couple photos of some of the paintings and sculptures on display. (There are a lot more than what I show here.) Looking at a realistic interpretation of bullfighters in their eyes – like that of Santiago Martín Sánchez, better known as “El Viti,” a torero from Salamanca who is immortalized in numerous works – I can’t help but wonder what causes them to risk their life to step into a ring with a dangerous bull. For some, I suppose it’s simply a way of life, handed down to them from their parents, grandparents, etc. For others, it could be a way out of poverty or a call to imitate their idols, just as others who idolize rockstars may pick up a guitar.

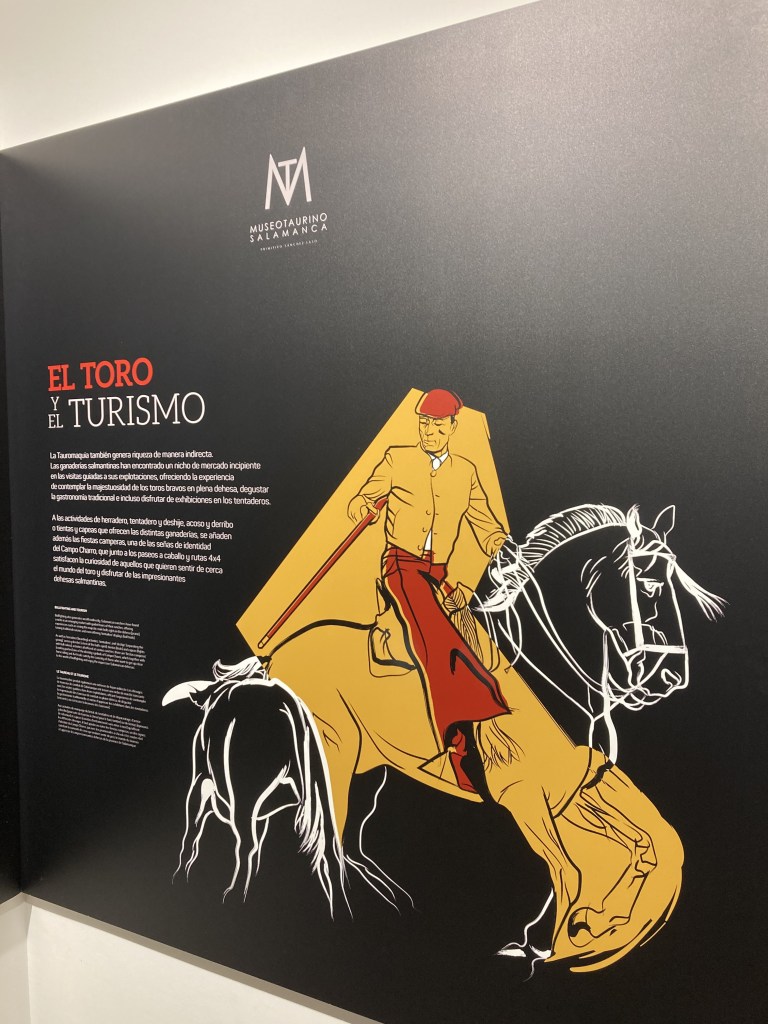

There are a number of panels placed throughout the museum that explain the history of bullfighting and its importance for the region for those of us who are not so knowledgeable on the topics. And some of the displays anticipate skepticism or even criticism of the fiesta nacional, giving facts that argue for its continuance. Here are some data that I found really interesting, along with some thoughts I have:

- Bullfighting accounts for a 1.6 billion euro economic impact in Spain. (I suppose this must include things like money spent at hotels and restaurants by bullfighting aficionados.)

- Annual revenue from the events is just under 209,000,000 euros.

- 200,000 people have jobs that depend on the industry, and 57,000 are employed directly in the business. (If that seems like a lot, keep in mind that those numbers must include not just the bullfighters and their teams, but the workers at the rings, those who raise the bulls, the workers who fabricate the costumes and tools, etc.)

- 25,000,000 spectators on average attend bullfights and bullfighting festivals annually, surpassing the number of theatergoers and moviegoers in Spain. (I have to admit that this figure seems a bit high to me, although I have no data to counter that statistic. I would have to think that they are including those who attend large festivals like the festival of San Fermín in Pamplona, which includes the running of the bulls.)

Just as bullfighting isn’t for everybody, maybe the Museo Taurino de Salamanca isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, either. Nonetheless, the students who chose to go with me to the museum at least had an open mind about it, and it seems like they learned something, even if they weren’t all swayed to study the topic further. Again, if you’d like to know more about bullfighting, but you don’t want the thrill (some would say “trauma”) of attending a bullfight in person, this is a gentle introduction to the industry. Like I said, the museum’s location is very convenient, and it can be seen in less than an hour. The space itself is quite cozy, with attractive brick archways. And at only 3 euros (and 2 euros for students and senior citizens), it’s really a small price to pay for an interesting museum that you can’t find anywhere outside of Spain (and maybe Mexico). The museum is open daily from 10:30 AM to 1:30 PM, and from 5:30 to 8:00 PM (except on Sundays).

If you can’t make it to Salamanca any time soon, here’s a nice video from a local television channel that shows what it’s like:

We didn’t attend an actual bullfight during our most recent trip, and like I’ve said previously, I don’t feel the need to attend another one, but we did take some pictures outside of Salamanca’s plaza de toros, known as La Glorieta, shown below. We were in town when it wasn’t bullfighting season, but it sounds like September is the main month for bullfighting in Salamanca, when a large bullfighting festival in honor of La Virgen de la Vega is held.

Would you go a bullfighting museum? Would you go to a bullfight? Let us know in the comments below. And if you enjoyed this post, please share it on your favorite social media. ¡Gracias!